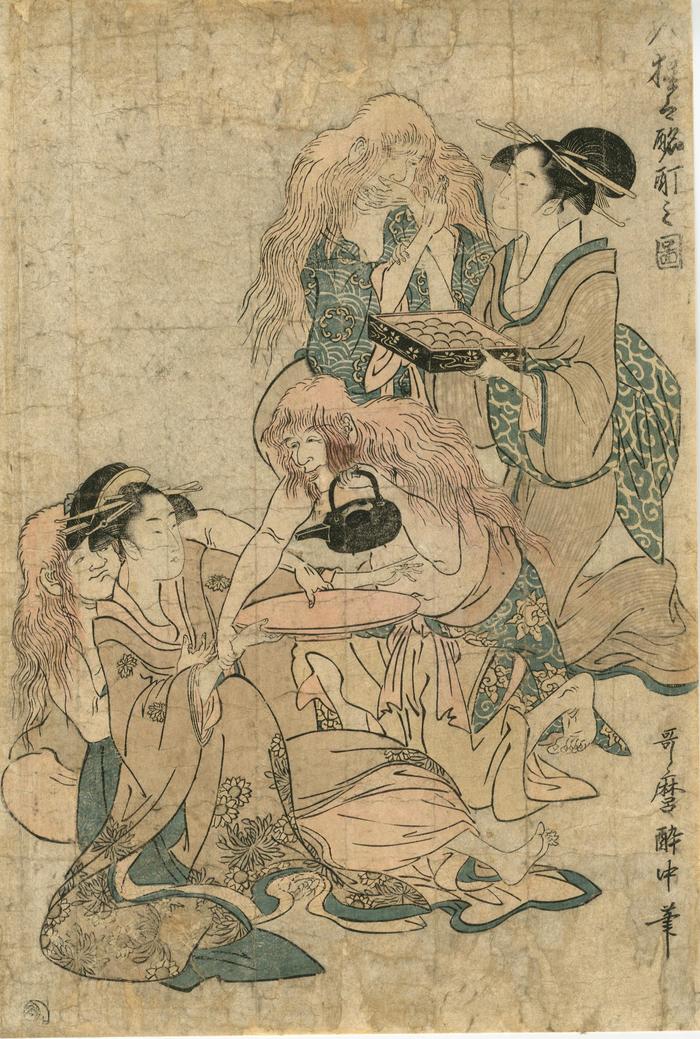

Kitagawa Utamaro (喜多川歌麿) (artist ca 1753 – 1806)

7 Imaginary Chinese Creatures (shōjō) in a Drunken State (Shichi-nin shōjō zuburoku no zu - 七人猩々酩酊之図) - left panel of a triptych

ca 1795

9.75 in x 14 in (Overall dimensions) Japanese woodblock print

Signed: Utamaro suichū (in a drunken state) hitsu

歌磨酔中筆

Publisher: Tsuruya Kiemon

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston - the full triptych The British Museum translates the title of this triptych as Picture of Seven Drunken Sake Sprites. This subject may also be a parody of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove (Chikurin no shichi-kenjin).

****

This composition is one of the most unusual and rarest among all of the works of Utamaro, an artist who some scholars believe is the greatest master of ukiyo-e of all time. The questions surrounding its origins are fascinating. Whose idea was it to produce such a piece? Is there a hidden message or symbolism we are unaware of? Its charm is obvious, but what lies below the surface? These are questions which may never be answered, but speculation is half the game, isn't it?

The shōjō (猩猩) has its origins in Chinese folklore. It is often described as being half man, half ape. That makes sense when one parses the meaning of the kanji characters: orangutan or sot. This gentle creature with long red hair is harmless and good natured, but has a particular liking for saké. The long, unruly red hair may draw a direct connection to orangutan. What is a bit puzzling is that there is an oft repeated belief that the hair of the shōjō could be used for an especially rare and valued red dye.

Robert Hans van Gulik in his The Gibbon in China: An Essay in Chinese Animal Lore traces on page 27 the origin of this creature, the xing-xing in China, back to the 2nd century. "In Japan the hsing-hsing... was promoted to a Wine Spirit, represented as a mythical animal with a fox-like face and very long, red hair, always drunk and dancing merrily. This shōjō motif frequently appears in Japanese applied art, and the great poet and art-critic SEAMI (世阿弥 1363-1443) devoted a Nō-play to it: there the shōjō, dressed in a magnificent brocade robe, executes a complicated dance around a huge wine-jar of green porcelain."

Van Gulik adds that it was reported that "wester barbarians" ate the meat of the xing-xing and used their blood as a dye.

Another source is Japanese Art Motives by Maude Rex Allen who notes on pages 50-51 that shōjō were said to live by or in the sea and come on shore to revel. Fishermen were said to lure them by placing large containers of saké near the water. Allen quotes a Japanese saying: As drunk as a shōjō as a warning to young people against overindulging in intoxicants. This differs little from Nancy Reagan's "Just say no to drugs!"

Allen notes on page 83 that a particular type of dragonfly, a bright red one, is named a shojo-tombo after the color of the hair of these mythical creatures.

****

Before we leave the topic of shōjō altogether we thought we would mention an unusual print by Sadafusa in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston: The Buddha of Sake Drinking (Sakenomi Nyorai). In it a shōjō is used as a stand-in for a buddha in an almost traditional presentation. The elaborately robed shōjō stands barefoot on a flowering lotus pod. In his right hand he holds a bottle of saké and with his left he holds a saké bowl behind his head as if it were a halo.

****

In 1796 the government issued a ruling that the names of beautiful women were not to appear on prints unless they were famous courtesans of the Yoshiwara or prominent geisha. Perhaps this print lacks the names for this reason or perhaps it was because the women chosen were meant to be more symbolic considering the scene.

****

Illustrated:

1) In color in a three page fold out in Ukiyo-e Masterpieces in European Collections 10: Museo d'Arte Genoa, I, supervised by Muneshige Narazaki, 1988, #151. They date theirs from 1789-1801.

2) There is the full triptych from the Vever Collection illustrated in color in Gimē Tōyō Bijutsukan, Pari Kokuritsu Toshokan (Musée Guimet, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, Henri Vever Collection, Huguette Berès Collection), editor Yamaguchi Keizaburō, 1980, pp. 180-181.

beautiful women (bijin-ga - 美人画) (genre)

Tsuruya Kiemon (鶴屋喜右衛門) (publisher)

Yūrei-zu (幽霊図 - ghosts demons monsters and spirits) (genre)